The Battle of Monte Cassino, this battle was also known as the Battle for Rome. It was a very costly series of four assaults by the Allies against the Winter Line in Italy that was held by the Germans and Italians during the Italian Campaign of World War II. The intention of this attack was a breakthrough to Rome.

At the beginning of 1944, the western half of the Winter Line was being anchored by Germans holding the Rapido, Liri and Garigliano valleys and some of the surrounding peaks and ridges. Together, these features formed the Gustav Line. Monte Cassino, a historic hilltop abbey founded in AD 529 by Benedict of Nursia, dominated the nearby town of Cassino and the entrances to the Liri and Rapido valleys, but had been left unoccupied by the German defenders. The Germans had, however, manned some positions set into the steep slopes below the abbey's walls.

Fearing that the abbey did form part of the Germans' defensive line, primarily as a lookout post, the Allies sanctioned its bombing on 15 February and American bombers proceeded to drop 1,400 tons of bombs onto it. The destruction and rubble left by the bombing raid now provided better protection from aerial and artillery attacks, so, two days later, German paratroopers took up positions in the abbey's ruins. Between 17 January and 18 May, Monte Cassino and the Gustav defences were assaulted four times by Allied troops, the last involving twenty divisions attacking along a twenty-mile front. The German defenders were finally driven from their positions, but at a high cost.

Plans and preparation

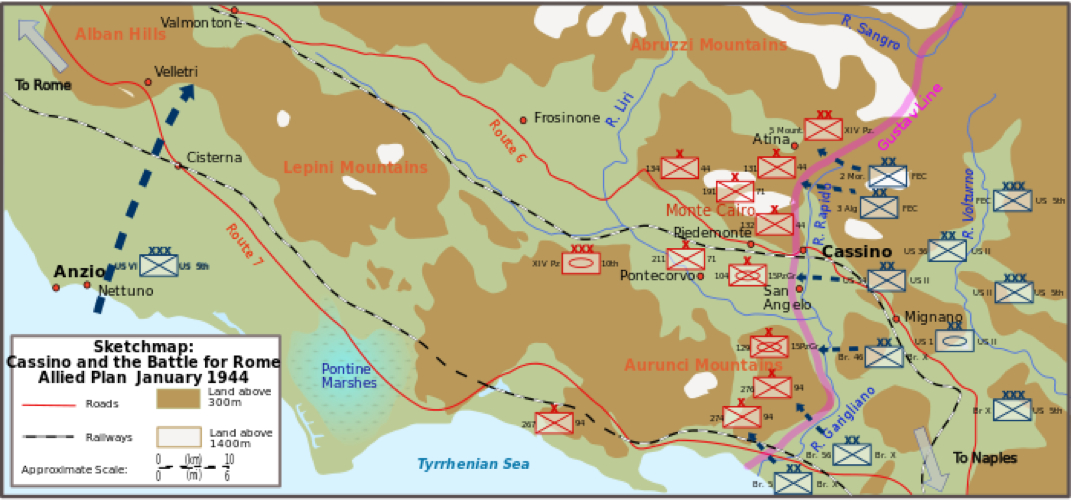

Battle of Monte Cassino order of battle January 1944

The plan of U.S. 5th Army commander General Clark was for British X Corps, on the left of a twenty mile (30 km) front, to attack on January 17, 1944, across the Garigliano near the coast (British 5th and British 56th Infantry Divisions). British 46th Infantry Division was to attack on the night of January 19 across the Garigliano below its junction with the Liri in support of the main attack by U.S. II Corps on their right. The main central thrust by U.S. II Corps would commence on January 20 with 36th (Texas) U.S. Infantry Division making an assault across the swollen Rapido river five miles (8 km) downstream of Cassino. Simultaneously the French Expeditionary Corps, under General Alphonse Juin would continue its "right hook" move towards Monte Cairo, the hinge to the Gustav and Hitler defensive lines. In truth, Clark did not believe there was much chance of an early breakthrough, but he felt that the attacks would draw German reserves away from the Rome area in time for the attack on Anzio where U.S. VI Corps (British 1st and U.S. 3rd Infantry Divisions) was due to make an amphibious landing on January 22. It was hoped that the Anzio landing, with the benefit of surprise and a rapid move inland to the Alban Hills, which command both routes 6 and 7, would so threaten the Gustav defenders' rear and supply lines that it might just unsettle the German commanders and cause them to withdraw from the Gustav Line to positions north of Rome. Whilst this would have been consistent with the German tactics of the previous three months, Allied intelligence had not understood that the strategy of fighting retreat had been for the sole purpose of providing time to prepare the Gustav line where the Germans intended to stand firm. The intelligence assessment of Allied prospects was therefore over-optimistic.

First Battle: Plan of Attack.

First assault: X Corps on the left, 17 January

The first assault was made on January 17. Near the coast, British X Corps (56th and 5th Divisions) forced a crossing of the Garigliano (followed some two days later by British 46th Division on their right) causing General von Senger, commander of German XIV Panzer Corps and responsible for the Gustav defences on the south western half of the line, some serious concern as to the ability of the German 94th Infantry Division to hold the line. Responding to Senger's concerns, Kesselring ordered the 29th and 90th Panzer Grenadier Divisions from the Rome area to provide reinforcement. There is some speculation as to what might have been if X Corps had had the reserves available to exploit their success and make a decisive breakthrough. The corps did not have the extra men, but there would certainly have been time to alter the overall battle plan and cancel or modify the central attack by U.S. II Corps to make men available to force the issue in the south before the German reinforcements were able to get into position. As it happened, 5th Army HQ failed to appreciate the frailty of the German position, and the plan was unchanged. The two divisions from Rome arrived by January 21 and stabilized the German position in the south. In one respect, however, the plan was working in that Kesselring's reserves had been drawn south. The three divisions of X Corps sustained 4,000 casualties during the period of the first battle.

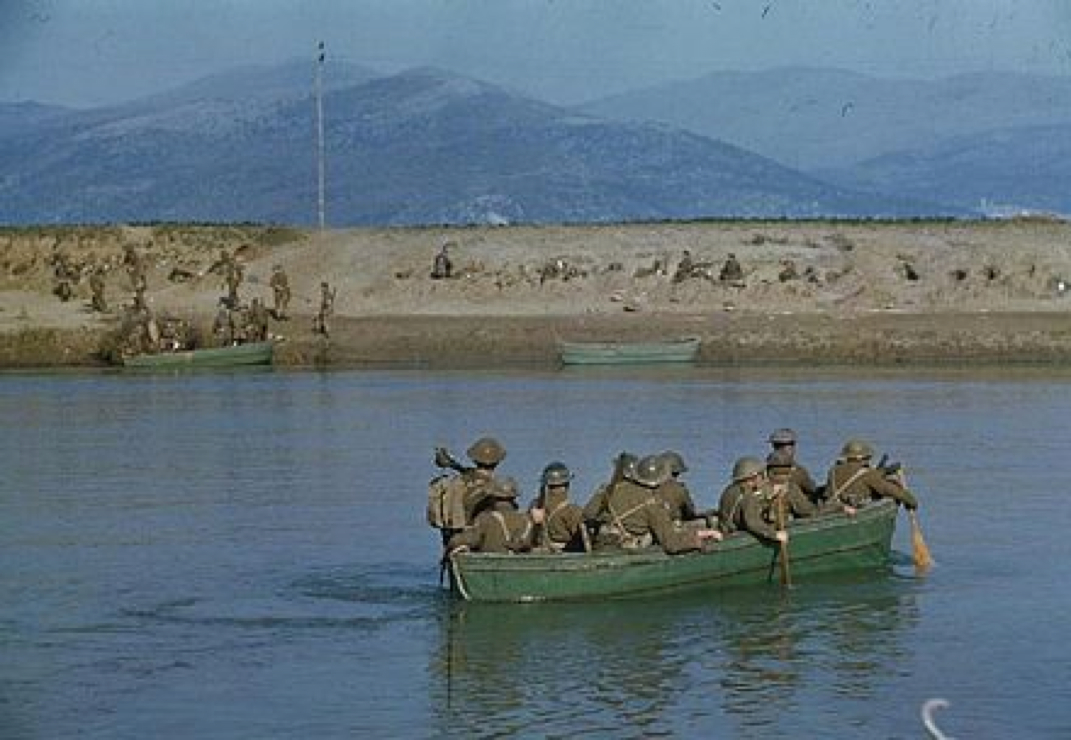

Royal Engineers cross Garigliano river on 19 January 1944

The central thrust by U.S. 36th Division commenced three hours after sunset on January 20. The lack of time to prepare meant that the approach to the river was still hazardous due to uncleared mines and booby traps, and the highly technical business of an opposed river crossing lacked the necessary planning and rehearsal. Although a battalion of the 143rd Regiment was able to get across the Rapido on the south side of San Angelo and two companies of the 141st Regiment on the north side, they were isolated for most of the time, and at no time was Allied armour able to get across the river, leaving them highly vulnerable to counterattacking tanks and self-propelled guns of General Eberhard Rodt's 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. The southern group was forced back across the river by mid-morning of January 21. Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes, commanding II Corps, pressed Maj. Gen. Fred Walker of 36th Division to renew the attack immediately. Once again the two regiments attacked but with no more success against the well dug-in 15th Panzer Grenadier Division: 143rd Regiment got the equivalent of two battalions across, but once again there was no armoured support, and they were devastated when daylight came the next day. The 141st Regiment also crossed in two battalion strength, and despite the lack of armoured support managed to advance 1 km (0.62 mi). However, with the coming of daylight, they too were cut down, and by the evening of January 22 the regiment had virtually ceased to exist; only 40 men made it back to the Allied lines. The assault had been a costly failure, with 36th Division losing 2,100 men killed, wounded and missing in 48 hours.

On February 11, after a final unsuccessful 3-day assault on Monastery Hill and Cassino town, the Americans were withdrawn. U.S. II Corps, after two and a half weeks of torrid battle, was fought out. The performance of 34th Division in the mountains is considered to rank as one of the finest feats of arms carried out by any soldiers during the war. In return they sustained losses of about 80% in the Infantry battalions, some 2,200 casualties.

At the height of the battle in the first days of February General von Senger und Etterlin had moved 90th Division from the Garigliano front to north of Cassino and had been so alarmed at the rate of attrition, he had "...mustered all the weight of my authority to request that the Battle of Cassino should be broken off and that we should occupy a quite new line. ... a position, in fact, north of the Anzio bridgehead". Kesselring refused the request. At the crucial moment von Senger was able to throw in the 71st Infantry Division whilst leaving 15th Panzer Grenadiers (whom they had been due to relieve) in place.

During the battle there had been occasions when, with more astute use of reserves, promising positions might have been turned into decisive moves. Some historians suggest this failure to capitalize on initial success could be put down to General Clark's lack of experience. However, it is more likely that he just had too much to do, being responsible for both the Cassino and Anzio offensives. This view is supported by General Truscott's inability, as related below, to get hold of him for discussions at a vital juncture of the Anzio breakout at the time of the fourth Cassino battle. Whilst General Alexander chose (for perfectly logical co-ordination arguments) to have Cassino and Anzio under a single army commander and splitting the Gustav line front between U.S. 5th and British 8th Armies, Kesselring chose to create a separate 14th Army under Gen. Eberhard von Mackensen to fight at Anzio whilst leaving the Gustav line in the sole hands of Gen. Heinrich von Vietinghoff's 10th Army.

The withdrawn American units were replaced by the New Zealand Corps (2nd New Zealand Division and 4th Indian Division) from the British 8th Army on the Adriatic front. The New Zealand Corps was commanded by Lt. Gen. Bernard Freyberg.

This is the ruins of the town of Cassino after the battle.